Lamentations of Ngami pastoralists

29 Jun 2015

Persistent outbreaks of the hard-to-contain Foot-and-Mouth Disease (FMD) in Ngamiland has had severe effects on cattle farming in the area.

The real victims are thousands of cattle farmers who depend on the animals for survival. Kobikoko Hange of Kareng village, south-west of Maun and Vepaune Moreti of Maun, are some of the victims.

“I have never sold a cow since 2007, yet I have over 100 cattle that could be benefiting me, and what a drawback this has turned out to be,” laments Hange in an interview.

He adds that he now depends on his children for a survival.

The farmer says while he appreciates government efforts to manage FMD, he reckons not enough is being done given that today the spread of the deadly disease has taken a new dimension, which requires proper and better control measures.

“The maintenance of buffalo and boarder fences is inadequate. The fence has not been maintained for a very long time now,” he complains. He adds that even the envisaged 100 per cent cattle vaccination is not feasible because the cattle population is too high. Most caretakers are elders who have very little energy to run after the animals.

Moreti’s view is that government must intervene because FMD has impoverished people in the area, and that farming is their lifeline and must be sustained by all means.

“Our boreholes have now collapsed because we can no longer afford to maintain them since we can’t sell our cattle anymore,” he adds.

Usually, the containment of contagious cattle diseases demands considerable efforts in quarantining cattle, vaccination, strict monitoring, trade restrictions, and possibly the killing of animals in the infected area.

That the Ngamiland community is one of the tribes which still value cattle rearing in Botswana, not only for their economic importance but also as culture and status symbol, cannot be overemphasised.

Besides economic benefits, cattle are reared for a number of other purposes including bride prize (lobola), inheritance, slaughtering for meat during family functions, and, of course, milk.

The main cattle rearing areas in Ngamiland stretch extensively from Maun in the east, throughout major villages of Sehithwa, Nokaneng, Gumare, Sepopa, Shakawe, up to Seronga on the northern banks of the Okavango River.

Although there are other activities of economic importance such as arable farming, fishing, and hunting, the livestock industry has been a major factor in the lives of the Ngamiland community for ages.

The only problem with cattle is that they are in an animal diseases prone area including the contagious bovine pleuro-pneumonia (CBPP) or lung disease.

Some of these diseases spread extensively and leave a devastating effect on the livestock industry in the entire Ngamiland region because usually during outbreaks, control measures demand restrictions on animal movement, cattle trade, quarantining, vaccinations, and possibly killing of animals in the affected areas.

In February 1995, for instance, farmers in the district suffered the contagious CBPP which culminated in the killing of the entire cattle population in the area to eradicate the disease in 1996.

That was after efforts to contain the spread of the disease by erecting three emergency cordon fences at areas such as Samochima, Ikoga, and Setata, to restrict livestock movements, proved futile.

After culling, government offered a range of compensation options to the affected farmers, and, since restocking the area in 1997, cattle numbers have rapidly increased to reach the current estimated population of 500 000, according to official statistics.

However, just as the communities in the area were beginning to enjoy livestock rearing once again, the district suffered brief spells of livestock disease outbreaks, especially FMD since 2007 until 2013.

The recent outbreak of FMD at Kareng in March this year, as usual, prompted the Department of Veterinary Services to place an immediate moratorium on the “movement of cloven-hoofed animals out of, within, and into Kareng, Semboyo, Makakung, Bodibeng and Sehitwa extension areas.”

Once again, local farmers were at loss after hoping to utilise the cattle market presented by the reopening of BMC’s Maun Abattoir.

The moratorium means that farmers will once again neither be able to sell their beasts commercially nor to the local butcheries, particularly because the off-take at BMC is too little given that the abattoir slaughters only 95 cattle per day.

Plant manager, Mothobi Mothobi, says this year their target is to slaughter 24 000 cattle and they have engaged farmers’ associations to ensure consistency in cattle coverage.

He says Maun abattoir is growing hence plans are underway to shut it down to allow refurbishment and upgrade to automated facility.

He says upgrading of the plant will improve efficiency and allow them to slaughter 120 cattle per day.

Although farmers appreciate government efforts to deal with the deadly disease, they feel more can be done given a seemingly unrestricted cattle movement.

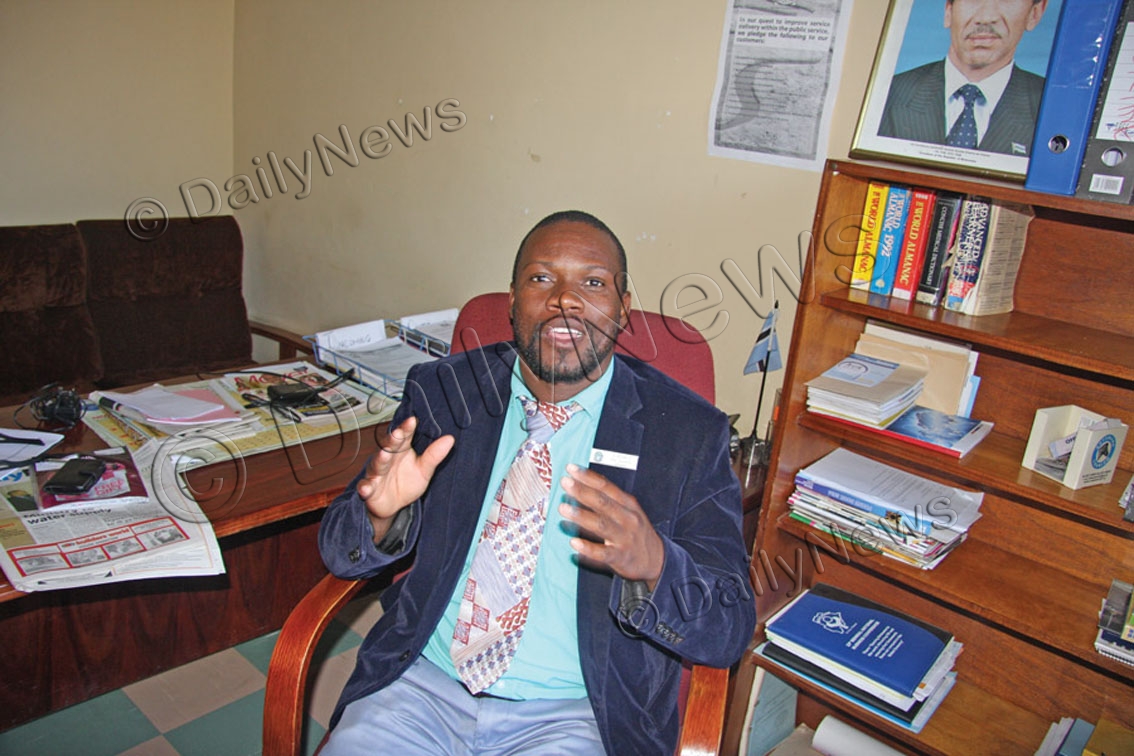

Meanwhile, in recent interview, Dr Obakeng Kemolatlhe from the Department of Veterinary Services said FMD was under control.

“Things are going in the right direction as the department has done its best to control and contain FMD in the affected areas,” he says.

Thus, he appealed to farmers to join hands with government so that all cattle in the affected areas are vaccinated.

Kemolatlhe says vaccination remains the only best option to control and contain the disease hence the need to conduct an effective exercise in which challenges such as leaving cattle to roam freely in search of pastures and water are avoided.

He says poor vaccination coverage was recorded in zone 2d around the Lake Ngami catchment which poses a threat of FMD resurgence.

Kemolatlhe also says efforts are on to maintain the buffalo fence despite shortage of transport which frustrates their work. Ends

Source : BOPA

Author : Esther Mmolai

Location : Maun

Event : Interview

Date : 29 Jun 2015